Communities with combined sewer overflows (CSOs) need solutions that will prevent flooding and reduce waterway pollution. One such solution is to bolster traditional gray infrastructure with green infrastructure. Green infrastructure (GI) refers to methods of  stormwater management that reduce stormwater volume by allowing it to be uptaken by vegetation, filtered by soils, or stored for reuse. Implementing GI programs (which includes trees, rain gardens, porous pavements, and green roofs) keeps polluted runoff out of municipal systems and out of waterways, rivers, and oceans.

stormwater management that reduce stormwater volume by allowing it to be uptaken by vegetation, filtered by soils, or stored for reuse. Implementing GI programs (which includes trees, rain gardens, porous pavements, and green roofs) keeps polluted runoff out of municipal systems and out of waterways, rivers, and oceans.

GI not only helps to manage stormwater, but also maximizes communities benefits. To explore these benefits and the practical side of implementing GI, including planning and funding, New Jersey Future hosted a virtual event, “From the Ground Up: Designing a GI Program.” Chris Sturm, managing director of policy and water at New Jersey Future moderated a discussion with Jessica Brooks, director of green stormwater infrastructure implementation at the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD), and April Mendez, the CEO of Greenprint Partners, a GI delivery partner that helps cities achieve high-impact, community-driven stormwater solutions.

After Sturm framed the conversation on implementation and the importance of public-private partnerships moving forward, Brooks discussed Philadelphia’s program for CSO control. The program, Green City, Clean Waters, seeks to protect and enhance Philadelphia’s watersheds by managing stormwater with GI. The 25-year program that began in 2011 sets recommended milestones for every 5 years that are in compliance with national regulatory obligations. By 2036 the city plans to have 10,000 greened acres—meaning that one-third of the CSOs will be managed through GI—and an 85% overflow reduction. The PWD is projected to spend more than 2.4 billion dollars over the next 25 years, with commitments made by many local stakeholders and partners to implement GI projects. The Green Stormwater Infrastructure Implementation Plan provides a road map for implementing projects highlighted in the CSO control plan, outlining action items in order to keep the program on track. In the plan, land area is broken down into rows (streets) and parcels (parks, commercial, facilities, schools, vacant land, residential, and campuses), which influence the types of GI that can be implemented in those areas. Through its public program, the PWD works with other city departments to incorporate GI into public space improvements. Incentivized retrofits allow PWD to access GI opportunities on residential and commercial properties. In order to fund the projects, Philadelphia modified its monthly stormwater fees, collected through a stormwater utility, to reflect each property’s relative contribution to stormwater runoff; properties with larger impervious areas that produced more runoff would pay the highest fees. The stormwater grant programs, SMIP (Stormwater Management Incentive Program) and GARP (Greened Acre Retrofit Program), also help develop more public-private GI partnerships. Finally, regulations on new development and redevelopment projects require the installation of GI. These projects have the advantage of having no upfront investment by the city. Development has a 1230 greened acre target, and has been the most successful so far. One reason why is because COVID-19 has slowed municipal projects down, while private projects have continued, with less budgetary concerns. Private landowner involvement has been critical to reaching GI development and stormwater runoff reduction goals in Philadelphia.

The Green Stormwater Infrastructure Implementation Plan provides a road map for implementing projects highlighted in the CSO control plan, outlining action items in order to keep the program on track. In the plan, land area is broken down into rows (streets) and parcels (parks, commercial, facilities, schools, vacant land, residential, and campuses), which influence the types of GI that can be implemented in those areas. Through its public program, the PWD works with other city departments to incorporate GI into public space improvements. Incentivized retrofits allow PWD to access GI opportunities on residential and commercial properties. In order to fund the projects, Philadelphia modified its monthly stormwater fees, collected through a stormwater utility, to reflect each property’s relative contribution to stormwater runoff; properties with larger impervious areas that produced more runoff would pay the highest fees. The stormwater grant programs, SMIP (Stormwater Management Incentive Program) and GARP (Greened Acre Retrofit Program), also help develop more public-private GI partnerships. Finally, regulations on new development and redevelopment projects require the installation of GI. These projects have the advantage of having no upfront investment by the city. Development has a 1230 greened acre target, and has been the most successful so far. One reason why is because COVID-19 has slowed municipal projects down, while private projects have continued, with less budgetary concerns. Private landowner involvement has been critical to reaching GI development and stormwater runoff reduction goals in Philadelphia.

So far, the PWD has exceeded its first 5-year target for GI implementation, and is expected to hit its 10-year target following the coronavirus pandemic. Furthermore, the PWD has undertaken a “triple bottom line” analysis in order to evaluate the total societal, environmental, and economic benefits of GI against the initial financial investments. Although this can be difficult to quantify, it can help compare a green approach to traditional infrastructure. Some benefits highlighted by the PWD include:

- Jobs in green stormwater infrastructure will help reduce the social cost of poverty.

- GI enhances recreation and the appearance of public places.

- GI will enhance quality of life, thereby increasing property values near installations.

- GI will reduce the effects of excessive heat in the summer.

- GI will have tremendous environmental benefits by improving air quality, offsetting carbon dioxide emissions, and restoring ecosystems.

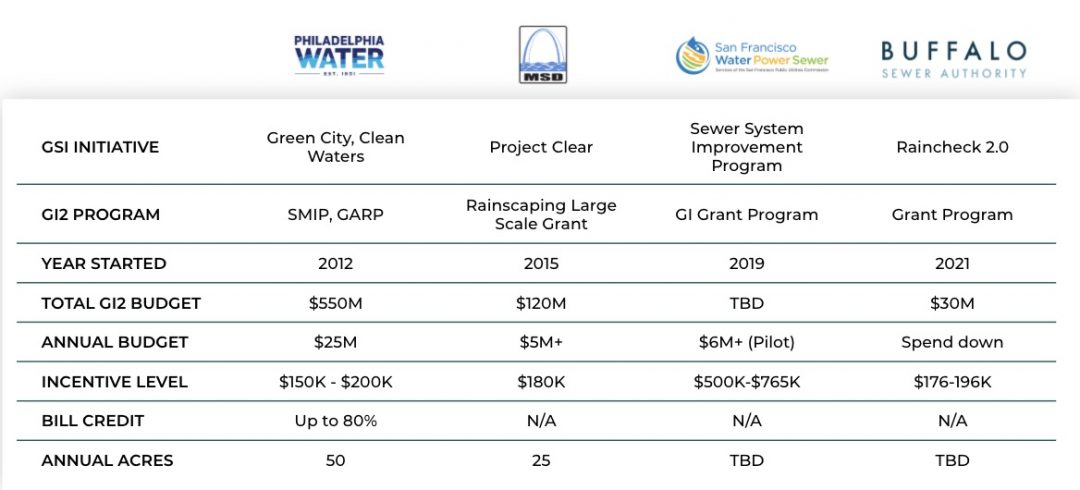

Following Brooks’ presentation, Mendez discussed strategies for the implementation of GI. When municipalities are first creating GI programs, they face many initial challenges, including difficulties to scale, not enough funding, slow rollout, and more financial risk for utilities. As a result, utilities often begin implementing piecemeal projects on public land or small scale residential programs to minimize these risks. This allows the utility to choose projects that are less complex and costly to begin with. Mendez explained that the main tools utilized to overcome barriers to scale GI were development regulations, private property incentives, public-private incentives, and outcomes-based contracting. Many cities, including Philadelphia, Buffalo, and San Francisco, are using multiple approaches for their sewer system improvement programs. Standard public-private partnerships (P3) programs allow the water utility to directly contract with a third-party administrator to manage the initiative and deliver greened acres on a pay-for-performance basis. The private partner is provided with the tools to develop and market the GI program, and contract with landowners to deliver greened acres. P3s help simplify procurement, thereby accelerating timelines for certain projects. Furthermore, the utility is able to control the budget for the GI project while distributing risk with the private partner.

Also central to this discussion was the importance of equity and inclusion in GI. There are a couple of ways to systemically level the playing field. First, Mendez says to focus on location. Install GI in communities that need it most, for example, low-income neighborhoods, communities of color, areas with health disparities, where there is a lack of green space, or high flood risk zones. Furthermore, utilities should saturate GI across these communities. According to Mendez, one of the “sweet spots” for GI retrofits are with anchoring institutions that serve low- and moderate-income communities, such as schools, public housing, local nonprofits and businesses, and houses of worship. These areas present sufficient impervious land for cost-effective GI solutions, while also impacting a large number of daily site users. Second, utilities should be intentional about who is involved in the planning, implementation, and stewardship of GI. Locals in these neighborhoods are key stakeholders in conversations regarding GI, and their priorities need to be considered beforehand. Third, utilities and private partners should design to maximize benefits based on community priorities besides simply considering stormwater performance. The final lever for increasing equity is providing job opportunities and training programs to residents in the community. Racial and economic segregation has been the lasting legacy of systematic racism in land use policies, and GI, if done right, presents one opportunity to reconfigure investment priorities for these groups.

During the current pandemic, it is crucial that municipalities and utilities plan and budget their GI projects to stay on track. As Brooks emphasized, it is important to set internal targets when creating a program to evaluate it and adapt it to future circumstances. Implementing sound GI programs can drive green job growth in these communities, provide clean air and water, reduce localized flooding, and enhance public health conditions equitably. Stormwater-related investments are pivotal for a more resilient future, and perhaps, we will be more prepared to “weather” future storms.