Sewage-Free Streets and Rivers partners reviewed all of the Development and Evaluation of Alternative reports from a community and quality of life perspective to ensure that communities have access to waterways and benefit environmentally and economically from these plans.

Here is what we found in the reports:

All of the municipal and utility permit holders will choose how they will measure the solutions to sewage overflows. They can either measure the solutions by demonstrating that they are capturing 85% of the flow or by using by using the presumptive approach based on reducing the number of system wide overflows.

All of the municipal and utility permit holders will choose how they will measure the solutions to sewage overflows. They can either measure the solutions by demonstrating that they are capturing 85% of the flow or by using by using the presumptive approach based on reducing the number of system wide overflows.

Presumptive vs. Demonstrative Approach:

Most permit holders have not officially selected an approach, but the general trend is toward an 85% capture, which equates to approximately 20 overflows a year, depending on the community. Our concern is that by focusing on the minimum requirement of the permit, other combined sewer overflows issues impacting communities like flooding, sewer back ups onto streets and parks and into basements, water quality, and toxicity will not be adequately addressed. Permit holders should select alternatives based on information that shows that not only will permit requirements be met, but community impacts of flooding, sewage backups, water quality and toxicity are also addressed.

Climate Change:

Although the permit does not require climate change or sea level rise to be considered when evaluating the alternatives, several permit holders and Supplemental CSO Teams considered climate change in their reports:

JCMUA, Ridgefield Park, Elizabeth, and Harrison included or discussed sea level rise.

CCMUA noted that climate change would be considered in the selection of alternatives.

Perth Amboy and PVSC’s Supplemental CSO Teams asked that climate change be considered in the evaluation of alternatives.

We recommend that NJDEP provide clear guidance on how permittees can include climate change data in the selection of alternatives so that they use the same baseline data for precipitation, storm intensity and frequency, and sea level rise. Permit holders reference 2004 as the design year, though baseline data within reports vary when discussing alternatives. These climate impacts could render CSO solutions ineffective or result in unintended consequences, unless they are taken into consideration in the design and selection of alternatives. For example, the Ridgefield Park report noted that sea level rise would reduce the amount of overflows. Less overflows into waterways could result in polluted water backing up into basements and onto streets.

Public Participation:

Other than attendance at Supplemental CSO team meetings, many of the permit holders and their consultant representatives had little to no interaction with the public when considering which alternatives to evaluate. This is despite a clear guidance document from the NJDEP recommending an ongoing public engagement process: The Supplemental CSO teams should not be considered as public engagement; rather, they should be treated as public engagement strategy sessions. These teams are designed to give municipal permit holders in-depth access to a key group of stakeholders with the goal of sharing the ideas developed in those meetings with the wider community–ideally, with the assistance of those stakeholder groups. Most of the reports indicated that the permit holders convened or participated in a regional and/or municipal Supplemental CSO Team, but they did not describe the preferences, questions, or any other input from stakeholder groups either at CSO Supplemental Team meetings or other public participation activities. We recommend that the permit holders be required to revise their evaluation of alternatives reports to include the following information to ensure that the preferences of Supplemental CSO Team members and the public are considered:

- A list of Supplemental CSO team meetings with the date, time, and location.

- A list of local LTCP process public meetings with the date, time, and location for each meeting along with the methods used for attracting attendees.

- Number of attendees for each meeting.

- A list of the types of people and organizations represented at the meetings, for example, community members, elected officials, community organizations, businesses or business associations, municipal employees, municipal consultants, home owners, etc.

- Agendas presented at the meeting as well as a summary of the preferences, concerns, and input gathered at the meetings.

- How the the Supplemental CSO Team was involved in a two-way conversation with the permittee beyond being a passive recipient of information.

- Explicit plans should be shared for how municipalities plan to engage directly with the public on the final report beyond the Supplemental CSO team meetings.

Green infrastructure (GI):

A thorough evaluation of GI is needed in order to determine the optimal amount of green infrastructure and select and site green infrastructure installations that produce the desired stormwater management and community benefits. Like all of the other alternatives, a thorough evaluation is needed to ensure that the technology is utilized properly.

The evaluation of green infrastructure in the evaluation of alternatives reports ranged from extensive to minimal. The CCMUA and JCMUA utilized a triple bottom line approach, which considers the social benefits of the alternatives evaluated. Some permit holders like Newark worked closely with community groups to understand their priorities. These permit holders also prioritized green infrastructure in a balanced approach. Other permit holders like North Hudson Sewerage Authority and Bayonne stated that GI will be implemented on a system wide basis or as a secondary alternative without any indication of what that actually meant.

We recommend that permit holders follow NJDEP’s “Evaluating Green Infrastructure: A combined sewer overflow control alternative for Long Term Control Plans” guidance manual related to modeling and explain the hydraulic and hydrological model used and the results. We recommend the reports include:

- Evaluate land uses, drainage areas and other community specific drivers and benefits to establish the goals and milestones for the GI program.

- Compile a GIS Database for GIS Parameters including flood prone areas

- Use one of the hydrologic and hydraulic modeling tools referenced by NJDEP (Arc Hydro, SWIMM, infor works) to model potential stormwater reduction volumes. The NY-NJ HEP worked with the City of Perth Amboy to undertake such an analysis for two model sewersheds, demonstrating that green infrastructure interventions that met preliminary feasibility tests and community support reduced peak stormwater volumes could be reduced by 20%.

We also recommend the use of a triple bottom line approach, as described in NJDEP’s “Evaluating Green Infrastructure: A combined sewer overflow control alternative for Long Term Control Plans” guidance manual to assess the selection of alternatives and articulate the community benefits of green infrastructure and a quantitative value of these benefits. The cost-benefit analysis should include the full range of community benefits.

We are concerned that permit holders like the North Hudson Sewerage Authority and Bayonne have stated that GI will be implemented on a “system wide basis” or as a “secondary alternative” without a quantitative measure (like gallons of stormwater captured or volume of stormwater reduction that shows how GI is contributing to the goal of 85% capture or 4 overflows annually) are not considering a meaningful GI program. We recommend that permittees be required to revise the evaluation of alternatives to include targets for gallons of stormwater captured or reduction of CSO volumes for GI. We are concerned that without a designated contribution goal reducing combined sewer overflows the GI component of the plan will be minimal and ineffective.

We recommend that the evaluation of alternatives describe the strategies that will be used to implement green infrastructure goals. For example:

- Identify all public land that can be utilized for GI (parks, schools, city, state and county owned lands and facilities).

- Develop a goal for stormwater capture from GI projects on private land as well as ordinances or incentive programs to achieve the goal.

- Choose locations for GI that will not replace existing green space with impervious cover.

- Plant trees as part of the GI plan.

- Use a cost analysis for GI based on economies of scale, procurement by quantity, and relate to cities of similar size and socioeconomic status.

- Implement GI in conjunction with community groups to ensure community engagement from the start of these projects and community acceptance.

- Ensure that consultants working on these plans are certified and experienced in GI design and construction.

Storage:

Storage is an alternative that all of the permit holders are considering. Some of the reports provide more detailed information on the proposed locations and dimensions of the storage tanks, tunnels or shafts being considered. We recommend that all of the reports include this information and that community members provide input on storage options being proposed and locations identified. It was unclear how the locations of the storage site were identified or if there had been any community input on the sites identified. We recommend that:

- The public have input into the selection of sites for storage.

- Land ownership be identified and verified.

- Identify the communities impacted and engage them in a two-way dialog on the proposed project.

- Dimensions of the storage tanks should be included in the reports and if they are surface or subsurface.

- Acquire private land for storage tanks rather than utilizing the traditional approach of bottom of the river end of pipe tank storage.

- Odor control should be discussed and evaluated.

- Include improvements on the surface that relate to needed amenities, like parks, parking, or GI opportunities.

Disinfection:

The Sewage-Free Streets and Rivers partners have concerns about the use of disinfection as a primary alternative to combined sewer overflows. To our knowledge, disinfection does not account for sewer back-ups and street flooding or the water quality that is in direct contact with residents. We are concerned that disinfection could have a negative impact on quality of life and cause health and safety issues because the water residents are interacting with will still be polluted. The bi-products are unknown as well as the long term impacts on the NY-NJ Harbor’s ecosystem. Disinfection on its own does not address solids. Holding tank location and land acquisition issues need to be addressed in addition to the safety of the public near disinfection systems. We recommend that NJDEP review the potential impacts disinfection could have on the quality of life and water quality in these communities.

Inflow and Infiltration Reduction (I & I):

I & I is a cost effective alternative that should be considered for further evaluation by all of the permit holders – documentation of the condition of the pipes and ways to address leaks should be made public and included in the reports.

Sewer Separation:

Spot separation can address local flooding issues and reduce overflows. Utilities, such as gas and electric, should coordinate to identify opportunities to separate sewers with new development or redevelopment and when other utilities are doing road work. We recommend coordination between utilities to reduce costs and maximize efficiency.

Evaluation of Alternatives:

We recommend that NJDEP require permittees to include a quantitative metric (such as gallons of stormwater capture or CSO volume reduction) to show the relative contribution of each alternative being considered for the LTCP. Some of the reports noted that GI would be implemented on a system-wide basis or implied that GI would be implemented as part of the plan but did not include the percent of CSO reduction or wet weather volume GI would account for in their evaluation of alternatives. The report should clearly show the options that the permittee is considering to reach the goal of 85% capture or 4 overflows annually add up and the percentage of CSO reduction each alternative will account for in the proposed plans.

The evaluation of alternatives should also include how funds will be allocated to ensure public participation for the selection of alternatives and implementation of the LTCP and statements by the permittees addressing plans to advertise, and monitor public participation in the selection and implementation of the LTCP.

Additional Alternatives to Evaluate:

- Water conservation was evaluated by several permit holders including Newark and Bayonne, but not all of the permit holders. This is a low cost solution that should be considered for further evaluation and included in the budget for the LTCP.

- Ordinances, zoning changes, and public education efforts to reduce stormwater entering the system were generally considered but should be considered for further evaluation as low cost solutions to CSOs and require budget considerations.

- Coordination with municipal, county and state government should be included in the LTCPs but was not mentioned in the evaluation of alternatives.

- Adaptive management was considered by one permit holder and would be beneficial to all of the permit holders to consider in their plans.

Comments on Specific Municipal and/or Utility Alternatives Reports focused on public participation:

Bayonne

Bayonne participated in the regional Supplemental CSO Team and formed a municipal supplemental CSO team. Specific details on the meetings, who was in attendance, agendas and preferences related to the alternatives were not included in the report.

The Supplemental CSO Team is hardly mentioned in the report, only being discussed briefly in section D.1.4, but the preferences of the CSO Supplemental Team are not mentioned.

There is no mention of outreach to public outside the supplemental team and no documentation of any preferences.

Bergen County Utilities Authority

On page 34, the BCUA LTCP discusses alternatives as they relate to “public acceptance” however, input from the Supplemental CSO team was not included. BCUA should hold community meetings where members can voice their opinions and concerns about each alternative.

CCMUA/Gloucester City/Camden City

The report considered public input and noted specific preferences of the Supplemental CSO Team related to several alternatives:

- The CSO Supplemental Committee has reinforced the desire among Camden stakeholders that the Final LTCP include as much green stormwater infrastructure as quickly as possible.

- The CSO Supplemental Committee noted that a satellite facility in the vicinity of G4 and G5 would impinge on the municipal park.

- The report noted that the Supplemental CSO Team would be included in the siting of satellite facilities.

- The feasibility of siting satellite facilities will be evaluated further in close cooperation with the neighborhood stakeholders and the CSO Supplemental Committee during the development of the Final LTCP.

Section 6.2 of the CCMUA LTCP states that climate change will be addressed in the final plan.

Section 6.4 described the triple bottom line approach being used to evaluate the alternatives.

East Newark

The Supplemental CSO Team is mentioned only briefly in section D.1.4, and the preferences of the CSO Supplemental Team are not mentioned at all. We recommend that a summary of feedback from the Supplemental CSO Team be included.

Elizabeth/Joint Meeting of Essex and Union Counties

Section 8 of the Evaluation of Alternatives report is dedicated to CSO Supplemental Team coordination. The report summarizes meeting notes, outlines community outreach activities and educational events such as Community Organization and School Events and discusses signage and notification systems. This is a good example of including community input in the report.

Guttenberg

Guttenburg did not consider public input or any input from a Supplemental CSO Team. The report speculates on the perceived desires of community members and private developers.

Section D.2.7 of Guttenburg’s report notes that Guttenburg will only be evaluating very limited GI measures which will only be implemented across three streets.

Harrison

Section A.5 discusses a local community group known as “Harrison TIDE”. It is important to state that this community group neither replaces a Supplemental CSO Team nor the community at large.

Jersey City

The report included preferences that were gathered through community meetings and from stakeholder groups related to green infrastructure and included some of this input into the evaluation of alternatives. This was a good example of including community input in the report related to green infrastructure.

The report noted community preferences related to green infrastructure but did not include the comments received or provide more specific details on the content of the meetings, attendance, or community represented.

We recommend more specific information be included in the report on the extent of the outreach, as well as the preferences of the Supplemental CSO Team and public related to the grey alternatives reviewed.

Kearny

Section C.2.2 of the report states that Kearny enlisted a local group known as Kearny AWAKE to give comments on the proposed solutions. It should be noted that this does not count as representation of the entire community.

Newark

Section D.1.4 of the report states that Newark has taken comments from the quarterly region Supplemental CSO Team meetings run by PVSC. These quarterly meetings are not sufficient for procuring public comments and preferences, and additionally, the comments that were made were not reflected in the reports. It is necessary to hold publicized and well-attended public meetings, and then provide the statements made by community members, not just a statement noting that community input was recorded.

Community groups have stated that no tanks should be installed and disrupt Riverfront Park.

Newark did hold 14 public meetings in partnership with community groups and its municipal action group Newark DIG, however the specific feedback from community members was not included or used in the alternatives analysis.

North Bergen Municipal Utilities Authority

Section D.1.4 of the report states that North Bergen has taken comments from the quarterly region Supplemental CSO Team meetings run by PVSC. These quarterly meetings are not sufficient for procuring public comments and preferences, and additionally, the comments that were made were not reflected in the reports.

Perhaps it was done accidentally, but it appears that North Bergen, after considering GI measures in the report, neglects to include GI as part of the final solution in section D.3.3. This warrants further investigation to ensure that North Bergen is, in fact, planning on implementing GI as part of their LTCP.

North Hudson Sewerage Authority (Adams St. and River Road)

The report noted that a workshop was held to evaluate the alternatives but does not indicate that Supplemental CSO Team members were included in the workshop or the preferences of the team.

North Hudson Sewerage Authority does own the land in the four communities that it serves. Although the reports states that it will seek GI to be used systemwide. It is unclear where the GI will be used. NHSA should include more specific information about their proposed plans for utilizing GI as an alternative, how sites were chosen, and how they are optimizing GI in the four towns. There is a need for the municipalities to be more involved in the development of NHSA LTCP.

Paterson

The terms “CSO Team”, “CSO Supplemental Team”, and “Supplemental Team” were not found in the City of Paterson’s report, indicating that input from these teams was not reported.

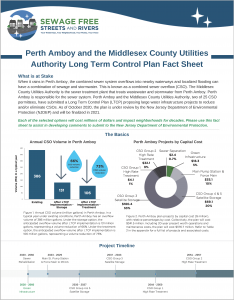

Perth Amboy/Middlesex County Utilities Authority

The report includes a few specific preferences and comments from the Supplemental CSO Team and how they were taken into consideration. Section 6.7 of the report is a place-holder for discussion and commentary from the Supplemental CSO team. We recommend that this section be added as well as additional information on how the Supplemental CSO Team and the public were engaged, and their feedback on the alternatives that were evaluated in the plan.

As with other permittees, the report states that it will seek GI to be used systemwide. It is unclear where the GI will be used. Perth Amboy has been the subject of several assessments by Rutgers University as well as the NY-NJ Hep that identifies and evaluates specific GI opportunities. The report should include more specific information about their proposed plans for utilizing GI as an alternative.

Ridgefield Park

Public participation captured by the Supplemental CSO Team meetings, Village Caucus Meetings, Earth Day event, and other outreach efforts. Of the six controls evaluated, favorability of the public was given a 15% weight though it was not identify what the public actually supported (seems like they are using general public perceptions to distribute weights) (see Table 7-31, pg 151).

Communities in New Jersey with combined sewer systems have submitted their plans to reduce combined sewer overflows into local waterways. The implementation of these plans could cost between $2.5 billion and $3.8 billion, and the proposed timeframes for implementation span 20 to 40 years. Facts like these can be found in the Long Term Control Plans but you need to know where to find them.

Communities in New Jersey with combined sewer systems have submitted their plans to reduce combined sewer overflows into local waterways. The implementation of these plans could cost between $2.5 billion and $3.8 billion, and the proposed timeframes for implementation span 20 to 40 years. Facts like these can be found in the Long Term Control Plans but you need to know where to find them.

“

“

Residents who live in these communities can read DEP’s comments to gain insight into the options being considered for their communities and if issues they care about, like climate change and flooding, were part of the review. Residents should submit preferences or concerns to their

Residents who live in these communities can read DEP’s comments to gain insight into the options being considered for their communities and if issues they care about, like climate change and flooding, were part of the review. Residents should submit preferences or concerns to their

Twenty-five New Jersey municipalities and utilities are developing plans to upgrade their century-old combined sewer systems. These upgrades will take decades to build and should serve communities for another hundred years. Thus far, the development of these plans has not required climate change to be taken into consideration.

Twenty-five New Jersey municipalities and utilities are developing plans to upgrade their century-old combined sewer systems. These upgrades will take decades to build and should serve communities for another hundred years. Thus far, the development of these plans has not required climate change to be taken into consideration. All of the municipal and utility permit holders will choose how they will measure the solutions to sewage overflows. They can either measure the solutions by demonstrating that they are capturing 85% of the flow or by using by using the presumptive approach based on reducing the number of system wide overflows.

All of the municipal and utility permit holders will choose how they will measure the solutions to sewage overflows. They can either measure the solutions by demonstrating that they are capturing 85% of the flow or by using by using the presumptive approach based on reducing the number of system wide overflows.

As a result of extensive efforts using SWMM and city buildings to shift public opinion on how CSO events might be tackled, Syracuse and Onondaga County have ended up with a cleaner and healthier Onondaga Lake, which now attracts more fishers, bald eagles, and boaters than in any time in recent memory. In fact, Onondaga Lake now even attracts performers and the community-at-large to the recently completed St. Joseph’s Health Amphitheater, a lakeside venue that is thriving due to the renewed cleanliness of the body of water upon which it rests. Let Syracuse and Onondaga County be an example; if we push for green solutions to CSOs, in combination with gray solutions, our communities will not only be greener, but also cleaner and more unified.

As a result of extensive efforts using SWMM and city buildings to shift public opinion on how CSO events might be tackled, Syracuse and Onondaga County have ended up with a cleaner and healthier Onondaga Lake, which now attracts more fishers, bald eagles, and boaters than in any time in recent memory. In fact, Onondaga Lake now even attracts performers and the community-at-large to the recently completed St. Joseph’s Health Amphitheater, a lakeside venue that is thriving due to the renewed cleanliness of the body of water upon which it rests. Let Syracuse and Onondaga County be an example; if we push for green solutions to CSOs, in combination with gray solutions, our communities will not only be greener, but also cleaner and more unified.